Our founder and CEO Jamie Strauss was invited to conduct a keynote interview this week at London’s 121 Mining Investment event with Evy Hambro, Global Head of Thematics and Sectors and Lead of the Natural Resources Equity Team at BlackRock.

The subject up for discussion was ‘Investing in the energy crisis economy’ and we’ve spotlighted our top five takeaways below, with Evy’s thoughts.

Investors are focusing on future-facing data to ensure accountability of the sustainable pathway.

“What is called ESG today we always used to think of as risk assessment. A company that had a bad environmental or social track record, or governance that wasn’t suited to benefit all shareholders, had a high discount rate attached to it. Companies that met all of those criteria and did them well had a lower discount rate attached to them. That’s just common sense.

I think we’ve now moved to an environment where all of that analysis is wrapped together within the ESG frameworks, and I think trying to commoditise ESG, which is happening in today’s data-driven environment, is very complex because some of it is subjective and therefore difficult to score. And so we obviously take note of the external data providers and the frameworks they provide, but we do our own analysis as well – going out and visiting the assets and meeting with management teams, and so on.

At BlackRock we have our own division that’s focused on stewardship. What we try to do is make sure the things we’ve always done are continued, but there’s a lot more information we have at hand today to be able to apply a framework to and link that to evaluation. In today’s world, that’s a great thing. But you can’t make yourself beholden to just the external data as there’s so much of it that is backwards-looking and if you only apply that data then you won’t back the businesses that are improving.

The real opportunity is to focus on the companies that are getting better. Whereas if we’re all just invested in the businesses that are already good, then we’re not going to provide the solutions for the future.”

There is clear evidence of strategic investment driving the cost of capital lower.

“It’s increasing clear that the cost of capital is declining for companies that are able to satisfy the needs of customers who are attached to the energy transition. So if you are an automotive Original Equipment Manufacturer and you are looking to lock in access to the supply of carbon-free produced commodities for example, then you are going to pay a premium, and you could provide capital to get access to those volumes. What we are seeing increasingly is companies coming to us and saying they have an agreement with a customer and that customer has agreed to pay an enormous amount for access to those volumes, and if you then calculate that back, that’s effectively a drop in the cost of capital for companies that can meet that criteria.

The volumes in that space today, depending on what commodity you look at, are still tiny and the demand is way bigger. So it’s not surprising therefore that there’s premium pricing – or the inverse of that, lower cost of capital – being paid for those volumes.

I think as time goes on and these volumes rise we will end up having transparent markets where commodities are traded in a certified form that allows them to represent the way in which something is being produced rather than necessarily just the purity of the end product. So maybe we have a carbon-free aluminium price or something like that in the near-term. I think that would be a fascinating change for the sector. And if that can happen, then people might start to pay a different price for the securities attached to the production. Because right now it’s a huge source of frustration that this sector continues to trade at a massive discount to broader market multiples, a discount to its own history, and an even bigger discount to what their customers trade at who are actually the suppliers of the technology and the infrastructure to the transition.”

The mining industry needs to speak in one voice to help incentivise investment.

“The industry, despite having consolidated, is still relatively fragmented. It rarely speaks in one voice. There isn’t homogeneity in terms of ESG reporting. Until the industry advances as one, it’s going to be difficult to overcome many of the capital challenges facing it.”

Senior mining companies are putting in options within junior miners to enhance long-term growth plans.

“I think what we’ve seen from the seniors over quite a long time now is maybe looking to put options into their pipeline. So we’ve seen many of the major mining companies take stakes in or buy individual projects, or earn-in agreements, and so on. And I think there had been a pause in that activity in 2011 to 2016 as companies sought to sort out their own balance sheets, to complete projects that they’d committed to build during the previous cycle.

So I think there’s been a natural repurposing and focusing on adding optionality to growth plans in the future. An incredibly sensible strategy. I think the beneficiaries of that will be the management teams in two generations and the shareholders who are patient enough to stay with those groups. So I’m excited about the value that’s being built into these bigger groups. So therefore there’s an incredibly important role for the market capital stack to play as they are feeding that project generation, and I think there is a big differential in terms of valuation.

One thing I think we’ve seen recently is the aspirations between what a project is worth have shifted, as I think there’s an increasing reality check about just how difficult it is to build things, just in terms of cost of capital and other complexities.”

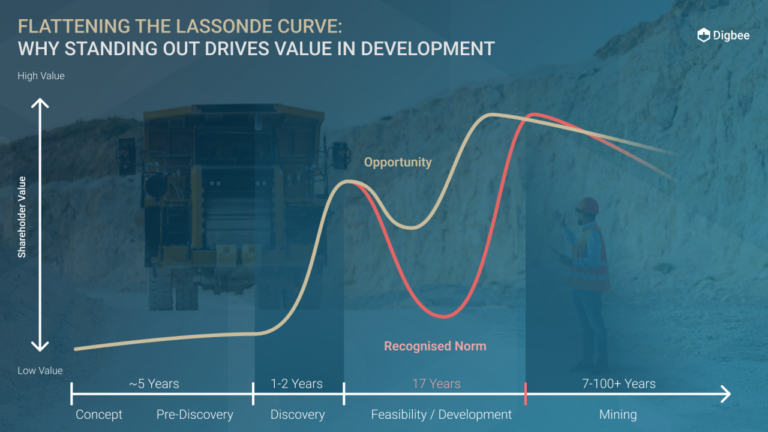

Junior mining companies represent huge investment potential.

“We look at the junior mining sector the in same way we’ve always looked at it. It’s an area of huge opportunity. Where are we going to get returns from? It’s going to be getting some of the midsize and junior companies right. But we’re very aware of the risks. It is a higher risk than going into one of the majors which is cashflow producing with a strong balance sheet – you have a smoother journey and its valued in a way that reflects that. Going into the juniors you’ve got to pick the right companies, and when to go in and out – and maybe back in again – during the lifecycle of a project.

So what we try to do is think about the management team, and their projects – hopefully a good combination of both. And we’re there for the capital journey through to production. But we choose our investments very selectively.”